"No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at their most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers." — Laurie Colwin

Almost every home boasts an eclectic mix of cookbooks, from one-pot meal guides to the stained, hand-scribed family heirlooms.

To me, a cookbook shelf has always seemed to be a subtle way of peeking into a person’s life. You can gain real insight and understanding about a person and how they spend their time in the kitchen, or with whom they share the secret or most prized recipes.

Always a household staple in my life, I’ve watched cookbooks and recipes pass to and from friends, loved ones and strangers. They hold a special place and fill a need for connection that can get lost in our busy modern lives.

Like so many elements of our modern life that are now common, to own a cookbook was once a privilege for only the wealthiest and the content and recipes defined lines between nobles, middle-class and the poor.

In 1825, the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin published this now famous quote in his book Physiology of Taste: “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es,” which translates to "Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are."

For me as a chef, this concept sparked a passion in me for culinary history, culture and food that would ultimately lead to my own eclectic collection of cookbooks and culinary tomes.

Historians will tell you that the oldest recipe ever found was scribed on the walls of the ancient Egyptian tomb of Senet. From the 19th century BC, it taught the people how to make flatbreads. The second oldest was found in Mesopotamia from the 14th century BC and described the making of Sumerian beer, referred to as "liquid bread." It was etched on clay tablets as part of a hymn to a goddess named Ninkasi, dedicated to beer.

The first recorded printed cookbook that is still in circulation today is Of Culinary Matters (originally De Re Coquinaria), written by Apicius, in 4th century AD Rome. It contains more than 500 recipes with many that feature modern Indian spices.

Apicius was a prolific and extravagant host. He squandered his wealth on eating and drinking and when he came down to the last of his wealth, he hosted an epic banquet. During the last course, to the horror of his guests, he poisoned himself.

Studying ancient cookbooks makes for a mystical journey through time. If you close your eyes, it's easy to imagine the cooks hard at work. The heat and flames of roaring fires, platters of the finest fare and the lavish ceremony of presenting intricate meals to the nobles and elite.

It's also interesting to discover the similarities of our trade across time periods and regions, but I’m totally enthralled by the differences. I’ve always found that these stories and history of the culinary world captivate and excite all the senses.

I really can’t pass up an opportunity to leaf trough any cookbook stash I find. I’ve found some excellent additions for my collection in the piles found at thrift shops, garage sales and flea markets.

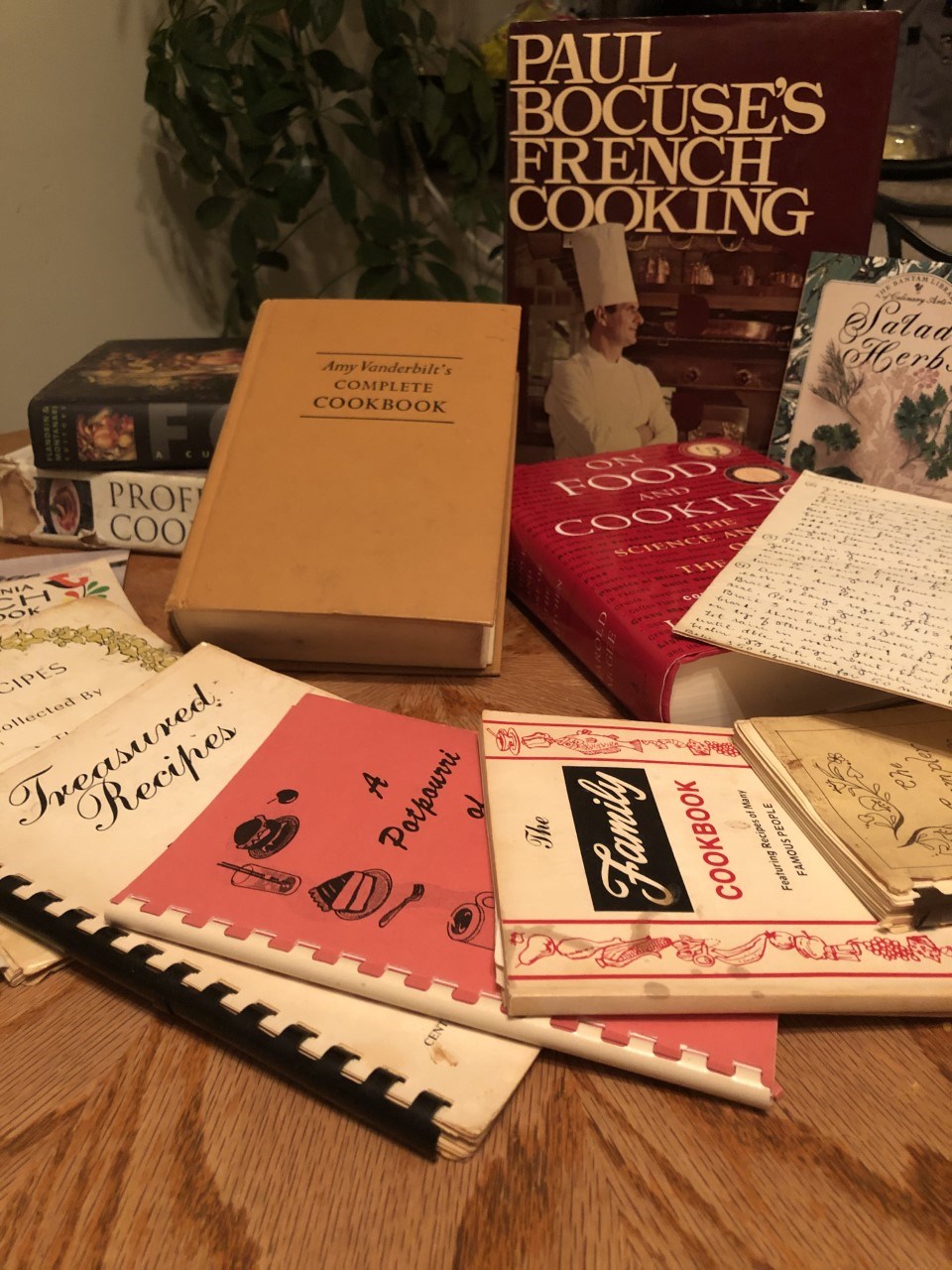

If I was to pick the three most important in my collection, they would be my copy of The Professional Cooking's fourth edition (the book that started my career), Paul Bocuse’s French Cooking and, my best find, the 1961 Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Cookbook, which has illustrations by a young Andy Warhol.

Before Warhol rose to fame as a pop artist in 1960s New York, he was a jobbing commercial and advertising artist. Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Cookbook features simple black-line illustrations done by a 33-year-old known as Andrew Warhol.

This book was published a year before his first solo art exhibition in 1962, which featured his now-famous Campbell soup cans.

This past month at Georgian College, our culinary program was the benefactor of a collection of books that spanned a lifetime of food and family. The Jenne family was kind enough to share a private collection of cookbooks and family recipes. As we sorted through the boxes filled with titles, we began to discover a sense of the family’s culinary history in a treasure trove of personal notes and unique pieces.

Many of the books were excellent examples of the time periods in which they were published. My favourites are the personal collection recipe books used as a fundraising tool.

These books speak directly to the people and communities that help curate the recipes and support the cause by helping put a future family heirloom together.

So next time you see a collection of cookbooks or find yourself wandering in the thrift store, take a peek at the cookbooks. You never know what treasures you might find.

And if you’re looking for something or just need a place to start, check out our Barrie Public Library. With more than 2,500 titles on hand, all you need is a library card and afternoon to start your passion.

Daniel Clements is the chef technologist at Georgian College’s School of Hospitality and Tourism