As I crossed the porch toward the side door of Chevy Halladay’s century home near Orillia, I had no idea what to expect. The door opened before I could knock, Chevy extended his arm to shake hands, and welcomed me into his home.

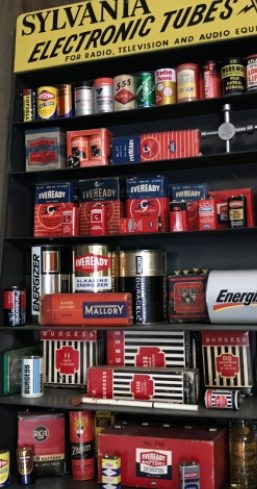

To my right was a small closet where I could hang my coat. I missed the hook, sending the coat to the floor. I was much too distracted to waste another second on hanging it neatly. To my left was a huge, free-standing mid-50s radio and TV tube testing machine stacked high with rare tubes, a six-foot-tall floor clock and radio with a built-in turntable, and a vintage Coca Cola vending machine. Each piece had been carefully restored for appearance and functionality.

A single step further into the room brought Chevy’s, and his wife Maggie’s, kitchen counter into view. Atop it were two partially restored radios, one a jumble of dusty tubes and a speaker early into the process, the other a spectacular and rare wood-cased Stromberg-Carlson, being prepared for final refinishing before being shipped to a friend in Bethesda, Maryland.

Don’t misunderstand. This was no hoarder’s enclave or home transformed into a ramshackle workshop. Their house is immaculate, and Maggie is on-side with Chevy’s mono-themed interior decorating style, yet it would be the understatement of the year to say there were a lot of radios and radio-related paraphernalia everywhere.

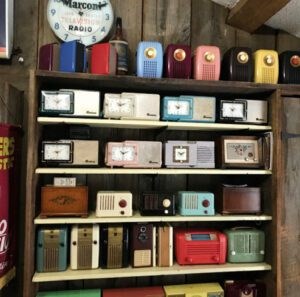

There was not an inch of wall that wasn’t shelved to display countless historic radios, or covered with hanging wall clocks that were used as promotional items by radio companies, steel promotional signs, framed advertising posters, or other memorabilia.

The floor was a controlled chaos of radios, cabinets containing radios, floor radios manufactured to look like free-standing grandfather clocks that housed radios and turntables, and end tables with built-in radios and sailing ship-styled radios on top.

This story is about more than radios. When I left Chevy’s home an hour later, I was exhausted, totally drained and overwhelmed by so many radios of every type. Information-overload enveloped me as I struggled to keep up with the significance of each model, its place in history, the development of radio technology, and the many, many stories.

Yet I was thrilled to have been allowed entry into Chevy’s world, to have met one of those people so passionate and knowledgeable and immersed in keeping the history of radios, and the culture that spawned them, alive for their enjoyment and to share with others.

We had met a few weeks earlier at my home. I was selling a solid-state JVC Matrix four-channel quadraphonic stereo amplifier and turntable unit, a first of its kind, which I spoke about in an earlier column from last June.

Chevy (yes, it’s his birth name; he is a child of the ‘60s, but I was too engrossed in his radios to ask the obvious) was the first to reply to my advertisement. Next day he drove from Orillia to Fonthill and bought the unit. Without pretension Chevy shared that he loved radios, and told the story of how he got hooked.

“I rented a house in Newmarket. It was a ‘50s house, and my partner at the time said, ‘We have a ‘50s house, a ‘50s trailer and a ‘50s car. We need a 1950s radio.’ I searched out two old men at their shop and found a ‘50s radio, then asked them if they would teach me [radio repair]. They said absolutely, and that’s how it all began.”

When Chevy moved north, he couldn’t conceive of moving all his radios into a contemporary house, so he purchased an 1872 brick century home.

“Now I’m in the house that I am because of a $20 radio.” Within minutes I asked if I could visit his home and meet his collection, and perhaps write a column.

Chevy’s been doing his radio thing for 20 years or more, and smiles when he recalls that his father forced him to attend college. He studied furniture production and design, which provided an appreciation for the aesthetics of radios, and an understanding of the attention to detail required to produce quality restorations.

“Little did I know 40 years later...”

Chevy drifts away for a second, then returns.

“Life has a plan for us, we don’t know why, or why we stick to things, but there we go.”

Chevy credits his friend and mentor, 88-year-old Paul Ross of St. Catharines, who for 50 years owned a TV repair shop in North Bay, for nurturing his passion for radios.

“I’m a complete novice compared to him,” he says. “I wish I could put a USB port from his brain into mine. If I ever get stuck fixing a radio, he’ll help me get it over the top.”

Our tour begins in a sitting room with nowhere to sit. Every room in the house except the bathrooms, every closet and bookshelf that I can see, is stuffed full of radios.

The next hour was a fascinating blur, a nonstop bombardment of radio facts peppered with trivia and anecdotes.

I saw the General Electric radio that Wally and the Beav listened to half a century ago, and the Philips 22RL798 from James Bond’s Diamonds are Forever.

Chevy has one of the first radios with remote control. It was manufactured by General Motors in 1932. The radio stood alone where ever you placed it, connected by wire to its dials built into a pedestal ashtray which could be positioned beside your sofa or chair. Ninety years ago one needn’t stand up to change stations or volume.

There was a shelf with a Sony Watchman, and various other radios with miniature TVs that you could take to the ballpark to watch the instant replays. Chevy explained the transition in electronics from radio tubes to mini-tubes to transistors to solid- state, then showed me one of the first Sony solid-state radios from the ‘70s with 13 different bandwidths.

The same shelf contained a Westinghouse Escort, a transistor radio that doubled as a flashlight and cigarette lighter, which led Chevy to lament, “Today they’re not as inventive, ingenious enough."

A highlight of his collection is a set of Electrohome radios from the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, handpainted with an Asian motif and design. He has five, and they are so rare that even finding information on them is difficult. Two of the beauties are sitting atop a similarly painted cabinet, which when opened displays an original, matching ‘50s television.

As we’re standing beside a row of lovingly restored floor-standing clock radios, I have to ask, “Will you ever sell any of these?”

Chevy explains how he keeps upgrading his collection as he learns more, how over time what were his top-end items have become his low-end stock, how his low-end is most peoples’ high-end, and how this is all self-financing, so yes, he does sell some things. Chevy is reluctant to use the word 'flip' when he describes his own connections to the radios.

“I got the bright idea that I wanted to collect as many (massive floor model clock radios) as I could. Now I love them so much, and I’ve restored them all, I’m keeping them all.”

As he continues, his tone becomes forbidding. He makes a categorical comment about his collecting philosophy.

“Most of the guys that are collectors now aren’t — they’re flippers. See, there’s not a radio in this house that doesn’t work. I buy them, fix them, get them all working. I don’t believe in having a radio that doesn’t work, I just don’t believe in having it sitting on a shelf and not working if I wanna go turn it on.”

Chevy later mentions his life has had a lots of ups and downs, and that he’s lost many people close to him. They’ve died. He keeps them alive through his radios, stating emphatically again, “I will not have a radio in the house that doesn’t work.”

There’s no mention of how this connection between his radios and lost ones works, and I don’t ask, yet my mind races to the conclusion that if one of Chevy’s radios ceases working, it might somehow extinguish a soul close to him.

The WWII-era Zenith Bomber shortwave radio, manufactured with revolutionary loctal tubes which allowed it to be transported in a plane or ship (the Clipper model) without the tubes falling out, was designed to give pilots and navy captains access to shortwave transmissions from anywhere in the world decades before the internet. Chevy has every model of this radio ever produced.

There are two Canadian-made Dionne Quintuplet radios, and a glistening white radio that would hang above a hospital patient’s bed. Inserting ten cents would allow you to tune the dial to locate just the right station for comfort or sleep. A different shelf contains the rarest of American Catlin plastic radios. The Catlins, whose casings could collapse if left in the sun too long, were made with plastic containing formaldehyde, leading to the death of many workers on their production lines.

Chevy has the Mickey Mouse children’s radio dubbed the “curtain burner.” The radio’s resistors were built into its cloth-wrapped cord, which frequently heated up enough to catch fire, ignite nearby curtains, and burn your house down.

The tour continued to a spare bedroom, where there was a DKE38, the low-quality, two-tube German propaganda radio with limited range nicknamed, “Goebbel’s snout.” Chevy showed me a photo of the uniformed Nova Scotian soldier he had purchased the radio from holding the DKE38 after smuggling it into Canada while returning from duty in Europe after World War II.

“A lot of Germans were listening to the Allies as they were coming closer. If the Germans caught you with this radio and the station was not in German, if there was any English or French, you would be assassinated on the spot. Done.”

There is simply no way the depth and breadth of this collection can be described in the space allotted this column.

As I prepared to leave, Chevy described the pitfalls a layperson might encounter when trying to get an antique or vintage radio repaired. I believe he was sincere when he said, “If (readers) have a family heirloom or something for their parents they can’t get it working, I don’t mind, I’d gladly help out.” He can be contacted at [email protected]

Chevy and his radios are a reminder that life is to be lived with passion, purpose and immediacy, to its fullest.

I loved my vintage bicycles back when there were 25 scattered around the house, but I realize now I was a piker compared to Chevy. He is so passionate, his experiences and interactions as he searches out his radios so rare, his life so absolutely directed. He lives and breathes his love of radios, and life, always looking forward to what tomorrow might bring for him and Maggie. What more could any of us need?

John Swart is a columnist for a sister Village Media publication, PelhamToday.