Editor’s note: The following is Part 1 of a two-part series. Part 2 will follow tomorrow morning. This story contains graphic accounts heard in court that might not be suitable for some readers.

Whatever innocence Barrie had was forever lost with the murders of Fred Shapcott, Ellsworth Beers, Pam Constable and Scott Seabrook in the fall of 1993.

The so-called Peel Street murders, which eventually included Shapcott’s death, effectively ended the notion that Barrie still bore any resemblance to a small town.

Shapcott, a 46-year-old Deluxe Taxi driver, was found stabbed to death in his cab at about 9 a.m. on Saturday, Oct. 2, behind a south-end business, Barrie Carpet Centre. City police said at the time there was no motive and no suspects.

On the morning of Monday, Oct. 4, the bodies of 85-year-old Ellsworth Beers, his 22-year-old granddaughter, Pam Constable, and her 28-year-old friend, Scott Seabrook, were found at Beers’s home at 138 Peel St. Their bodies were discovered when Constable didn’t show up for work that day.

Robbery was believed to be the motive, but fear understandably gripped this older Barrie neighbourhood, despite police saying there was no evidence to suggest the killer would strike again.

Members of Beers’s Christian church, in fact, expressed fears it could happen again.

The killings left Barrie residents in shock, for want of a better word.

The Peel Street murders became a national story in a city best known for its population growth, and as a gateway to Muskoka cottage country for Greater Toronto Area residents.

By the end of that week, Barrie police said they had several suspects in the deaths of Beers, Constable and Seabrook — but they were a long way from making an arrest.

Other lurid details about Peel Street also began to emerge.

Robbery was still the motive, but two of the victims had been bound by their hands and feet. One had a scarf around his or her neck. No weapon had been found, police said.

By mid-October, Barrie police had the autopsy results but declined to release them.

Later in the month, police said the Peel Street victims had been strangled and stabbed to death.

October’s end still had police saying they hadn’t found any connection between Shapcott’s death and the Peel Street killings.

In early November, police were looking for a light green, mid-sized, North American-style car in connection with Shapcott’s death, but investigators said the car’s driver was not necessarily a suspect.

Later the same month, Barrie police noted the overtime officers were working because of the homicide investigations. Police later said investigators racked up 4,000 overtime hours in the five months following the killings.

By early December, city police said there had been approximately 200 tips and that investigators had narrowed down the list of suspects.

There was little progress, at least publicly, during the police search for the killer, or killers, as 1993 came to a close.

Early in 1994, police said two officers were poring over evidence and statements from the case.

Police had a profile of the killer, from an Ontario Provincial Police specialist, but it was not released to the public.

A link between Shapcott’s killing and the Peel Street murders had still not been publicly established by police.

In early February, police said there were no new leads in Shapcott’s death, and they were still awaiting forensic results from his taxi.

By that time, police had recreated the crime scene, the place where Shapcott was last seen alive, and even hypnotized one witness in an attempt to gather new clues — any clues.

The trail had seemingly gone cold, very cold.

That all changed in early March with the Barrie Examiner headline, in large, black, bold letters: ‘Arrest at last.’

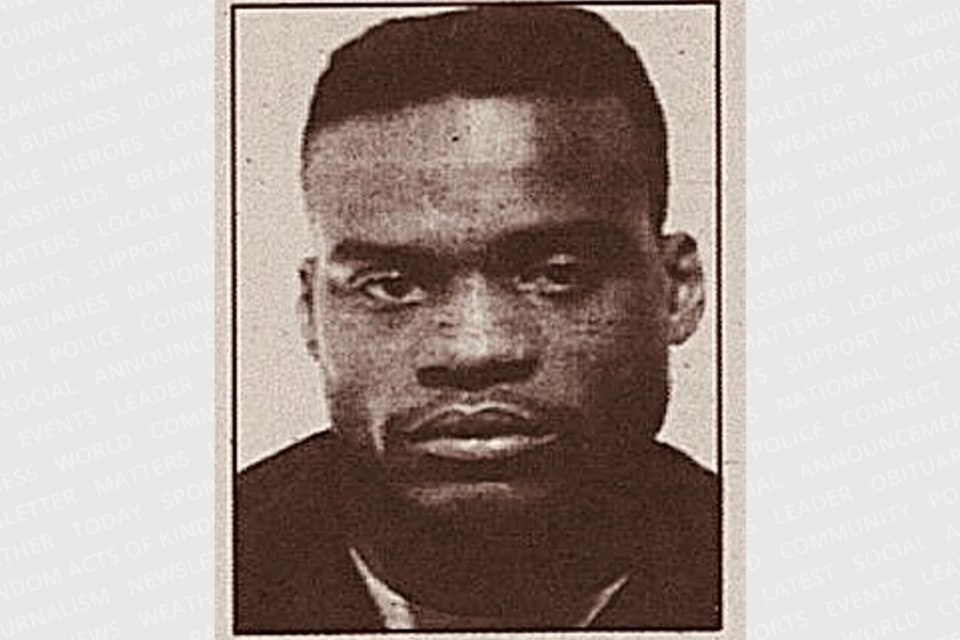

Eric Fitzgerald Ross, 28, was arrested and charged with four counts of first-degree murder and two counts of attempted murder. It was the incidents relating to the latter charges that eventually solved the Peel Street murders.

At about 3 a.m. on Tuesday, March 1, 1994, a taxi pulled up in front of a Fox Run home in Barrie’s Letitia Heights area. Ross went inside and, minutes later, a teenaged boy ran screaming from the house. A neighbour or the cabbie called police.

Police called the incident a “random” stabbing of a 40-year-old woman and her 15-year-old son. Both were taken to Royal Victoria Hospital. Robbery was the motive, according to police.

Ross, unemployed, a Barrie resident since 1973 and originally from Barbados, was arrested.

Police said he was not a prime suspect in the Peel Street murders until that Tuesday — despite being interviewed eight previous times by investigators. Ross had offered himself to police as a possible witness to the Peel Street murders, though a court later heard that might have been to throw investigators off his trail.

At that point, police released new details about what happened on Peel Street that October weekend.

One was that Shapcott’s death and the Peel Street killings had been tied together by police since early February.

Ross had been in the Peel Street area on the night of Oct. 2 and randomly chose the Beers home. The motive was robbery, to buy drugs, including crack cocaine.

More shocking was that all three Peel Street victims were strangled, Beers and Seabrook were stabbed, and Constable had been sexually assaulted.

A March 10 story in the Barrie Examiner had Ross denying “everything” through his lawyer, John Hill. For several years while awaiting trial, Ross also maintained his innocence.

It wasn’t until the spring of 1997 that Ross came to trial, in Bracebridge, ostensibly to have a jury pool impartial enough to give him a fair trial. Assistant Crown attorney Mike Martin prosecuted the Peel Street murder case. Ross was tried separately for Shapcott’s death.

On April 2, 1997, Ross pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder, but he admitted he caused the deaths of Beers, Constable and Seabrook. He offered to plead guilty to manslaughter at the beginning of his trial, but Martin declined and went ahead with the first-degree murder charges.

Court heard that on the day he was arrested, March 1, 1994, Ross confessed to police in videotaped statements that he had committed the Peel Street murders. Ross said he was stoned, wasted, at the time of the killings.

He said he walked past the Beers home on his way to get snacks for a friend at a nearby party. He said he had left a Grove Street address at about 9 p.m.

Seabrook was talking to Constable outside a house, in the driveway. Ross grabbed Constable, held scissors and a knife to her throat and forced her and Seabrook inside, court heard. He made Constable tie up Seabrook. Ross said Constable begged him to spare Beers, who was asleep upstairs.

Seabrook was then killed, court heard, stabbed by Ross numerous times with scissors.

Ross then sexually assaulted Constable, tied her up and strangled her, court heard. His semen was found in Constable’s underwear.

Ross said he grabbed an “acetate torch thing,” hit Beers with it, went downstairs to get a knife, and then stabbed the elderly man several times in the throat. Later, a heavily dented propane cylinder was found, used by Ross on Beers to shatter his skull.

Ross said he stole more than $200 in cash before leaving the Peel Street home. During the trial, court heard drugs had played a prominent role in his behaviour that fatal weekend.

On May 6, 1997, Ross took the stand in his own defence. He testified he was so high on crack cocaine that he remembered nothing about the Peel Street murders. He wept on the stand. Hill said Ross suffered from brain damage, too.

The next day, May 7, 1997, Ross said he was disgusted with himself, wished he was dead and that he didn’t know why he killed Beers, Constable and Seabrook.

But Martin methodically took Ross apart in the courtroom, showing the contradictions and untruths in his testimony — some of which were confirmed by Ross himself.

On May 28, 1997, the jury needed just three hours to convict Ross on three counts of first-degree murder.

Justice Robert Weeks called Ross a “savage and methodical” killer.

Ross was sentenced to life in prison, with no chance of parole for 25 years. He was eligible for parole on March 1, 2019, 25 years from the date of his arrest. He remains in prison, according to the Parole Board of Canada.

In a Barrie courtroom on June 11, 1998, Ross pleaded guilty to murdering Fred Shapcott in October 1993 and, five months later, to trying to kill a woman and her son at their Fox Run home on March 1, 1994.

Ross was sentenced to life in prison for Shapcott’s death, with no chance of parole for 10 years, and received two 15-year sentences for the attempted murders of the woman and her boy.

Those sentences, along with those from the Peel Street murders, were to run concurrently.

Justice John McIsaac added a line to the killer’s file: “I recommend you never be released from prison,” unless Canadian correctional services can guarantee Ross will have no access to drugs.

Through an agreed statement of facts, court heard the gruesome details of Shapcott’s death and the Letitia Heights incidents.

Ross had tried to get drugs on the night of Oct. 1, 1993, but he could not, and he called a cab to the corner of Innisfil Street and Essa Road, driven by Shapcott.

The cabbie was told to go to the rear of Ross’s place of work, Manley Steels near Big Bay Point Road, where Ross said he wanted to pick something up.

Shapcott was attacked there with a knife, repeatedly stabbed in the face and neck, and beaten.

With Shapcott in the back seat, Ross drove the taxi to a location behind a Bayview Drive business, and then walked home.

He had robbed Shapcott of $170, court heard.

Shapcott was found the next morning by another cabbie who had been looking for him because he was missing.

Drugs also played a role during the Fox Run incidents five months later.

Ross had borrowed $20 from a woman’s husband in a bar on the night of April 30, 1994, and then went off with a friend to use cocaine.

Ross came across the same man later than night, refused to pay him back the money and took off with the man’s coat.

Later that night, or early during the morning of March 1, Ross ended up at the man’s home.

The man’s wife was brutally stabbed in the neck, her voice box permanently damaged by a rotating knife and scissors, before she was strangled unconscious, court heard.

Ross then turned to the woman’s son, who was sleeping in the basement, using a hammer and scissors Ross had found there. Ross was looking for money, but the teen had none.

The 15-year-old boy got away and went running to a neighbour for help.

Ross answered the door when Barrie police officers arrived.

The mother and son were taken to the Barrie hospital. He was treated and later released, but the woman’s stab wounds to her throat required five hours of surgery at Toronto General Hospital.

A crucial link between Peel Street and Fox Run was that police determined semen samples found at the homes were a match. Both women had been sexually assaulted by the same man.

Martin described Ross’s furor on Barrie residents as “a very sad coming of age” for the rapidly growing city.