(Editor's note: This is part one of a two-part story about Herb Drury, a local hockey star, who went on to represent the United States at two Olympic Games.)

The very first Winter Olympics, held in the French resort town of Chamonix the last week of January and first week of February, 1924, was a small affair compared to modern Games.

But in the middle of it all, leading the American team into the “stadium” (which was a centrally located giant outdoor ice rink in the shadow of Mont Blanc) was an athlete who was born and raised in North Simcoe.

Herbert John Drury, the firstborn of Edward and Margaret (McColl) Drury, was born in the former Medonte Township in 1894.

The family moved to Midland the following year, where Herb’s four younger siblings were born. Tragedy struck the family in 1913 when Edward died, leaving Margaret to raise five children ranging in age from four to 18 on her own.

By then, Herb was already garnering his share of newspaper headlines.

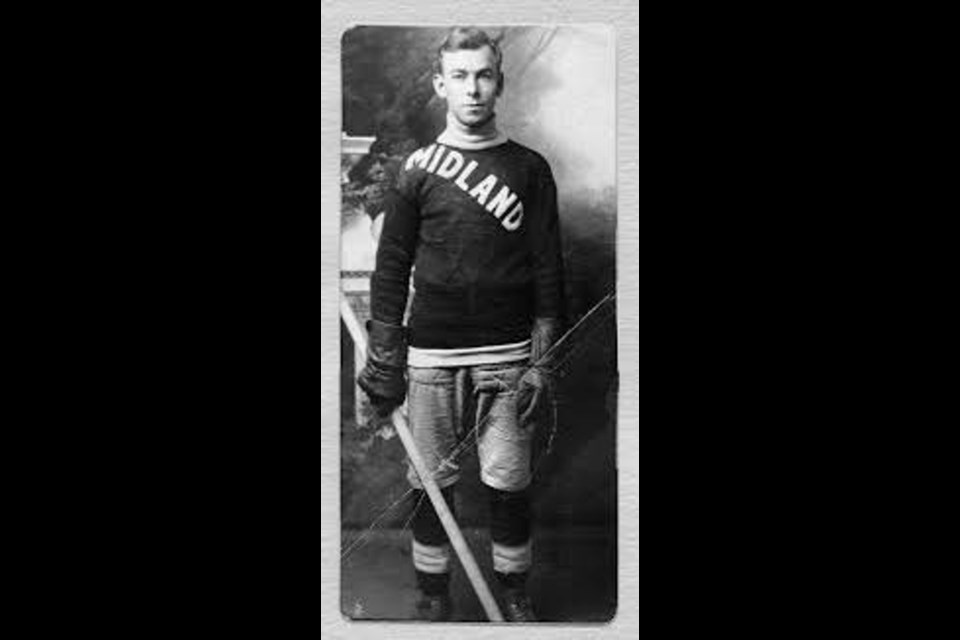

The speedy youngster was the star of the Midland junior team. Word of his combination of speed, puck-handling and scoring ability quickly spread throughout the province.

But facing tough times, Margaret was unable to provide for her family, and the siblings had to be split up.

Daughter Mary was sent to live with an uncle in Saskatchewan, while Margaret took her youngest kids, sons Morley and Harold, to live with her in Southern California.

Given his hockey promise, Herb was sent to live in Port Colborne, then a hotbed of amateur hockey in the province.

It was while playing for the local team that Herb was noticed by Port Colborne native Roy Schooley, who had moved to Pittsburgh over a decade earlier to bring the game to the United States.

Schooley became involved with the Duquesne Gardens, an arena housed in a local casino.

The team he managed, the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets (with a half dozen fellow Canadians in the lineup), became one of the United States’ first professional hockey teams.

With artificial ice and a playing surface over 50 feet longer than Canadian rinks at that time, the Yellow Jackets were a fast group, and the small (5’7”/140 lbs.), but swift Drury was a natural for the team.

Drury played in Pennsylvania for several seasons, but it was well known at the time that the Pittsburgh players were paid for their efforts. Banned as a result by the governing body of amateur hockey in the province, the Ontario Hockey Association, and denied reinstatement, Drury decided to stay in the Steel City, which was to be his home for almost fifty years.

When the United States passed the Selective Service in May of 1917, Drury was drafted, and enlisted with the Army.

At the end of the war eighteen months later, Drury — who was never deployed — was granted the opportunity to apply for American citizenship as part of his discharge.

That allowed the U.S. Olympic Association to add Drury to the roster (six of the team’s members were naturalized Americans) of its first-ever hockey team at the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp.

A combative player on the ice, possibly because of his size and skill, Drury nearly missed taking part in the Games when he attacked an official during an exhibition game with the Winnipeg Falcons in March.

But after appealing his resulting suspension, Drury was allowed to join the team when they left for Belgium in early July.

The Americans lost 2-0 in the semi-final to eventual gold medal winners Canada (represented by Winnipeg Falcons, who had captured the Allan Cup) .But while the American squad faltered against the Canadians, Drury drew raves for his play as his team took home the bronze.

D.M. Fox was, like Herb and Morley Drury, raised in Midland. He has written two books of historical baseball fiction partly set in North Simcoe. “On Account of Darkness: the Summer Ontario Baseball Broke the Colour Barrier,” and “Severn Sound: a Big Leaguer Comes to Port McNicoll,” are both available on Amazon/Kindle, and most ebook platforms.