Math skills are not usually listed on a reporter’s resume.

Many journalism industry professionals make concerted efforts to avoid numbers. In fact, our Canadian Press style dictates we don’t even use Arabic numerals for numbers under 10 (like any grammar rules, there are approximately 47 exceptions to the rule).

But numbers are important in covering many stories from municipal to federal realms.

You probably know a lot about the U.S. electoral college and that magic 270 number if you did any Internet surfing last week.

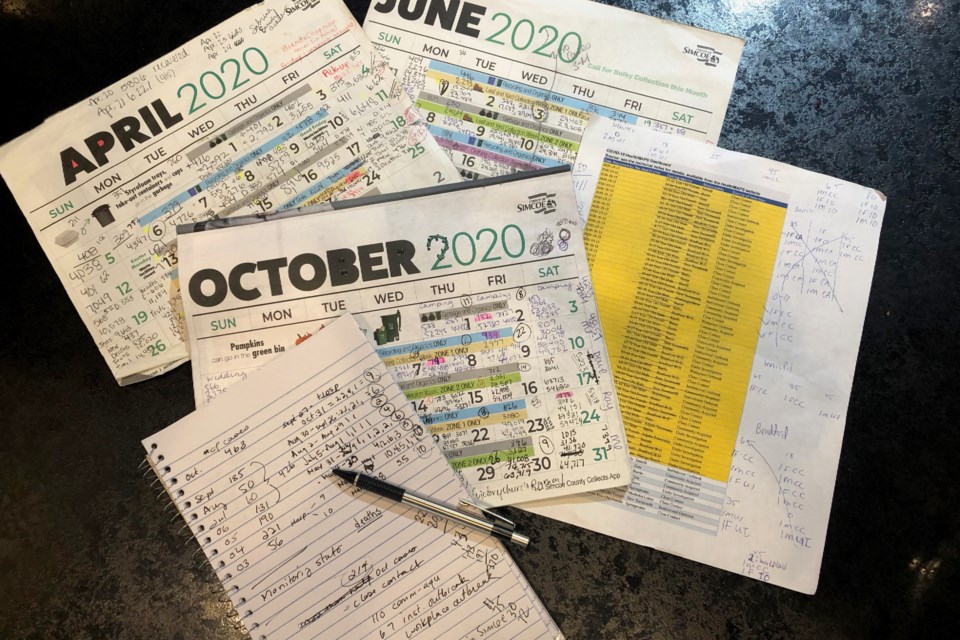

As I’ve been covering the pandemic for Collingwood, numbers stories have been a twice-daily task for me. Over the last seven months I’ve learned just how personal math can be.

50 – the number of people who have died in Simcoe County and Muskoka Region with COVID-19 since March.

3,233 – the number of people in Ontario who have contracted COVID-19 and died as a result

Though math and numbers typically sell themselves as finite and absolute, reporting COVID-19 has reminded me they can also be controversial.

1,328 – the number of cases reported on Nov. 8 and the highest number of cases reported in a day.

There are those who believe we are fear mongering in noting daily case records or that we’re not telling the whole story.

Math can provide context.

41,268 – the number of COVID-19 tests reported processed on Nov. 5

3.7 per cent - the per cent positivity rate

45.4 cases per 100,000 people – the average incidence rate in the province for the week of Oct. 29 to Nov. 4

But I don’t think math can ever tell the whole story. One story can’t tell the whole story of a global pandemic that has changed nearly every part of the world in less than a year. A virus that has revealed dark corners of our universal health-care system’s flaws, that has seeped into our minds to push our mental health to its limits and, in some cases, beyond.

Math, numbers, rates, and peaks on a graph tell part of the story, though. And many parts make a whole.